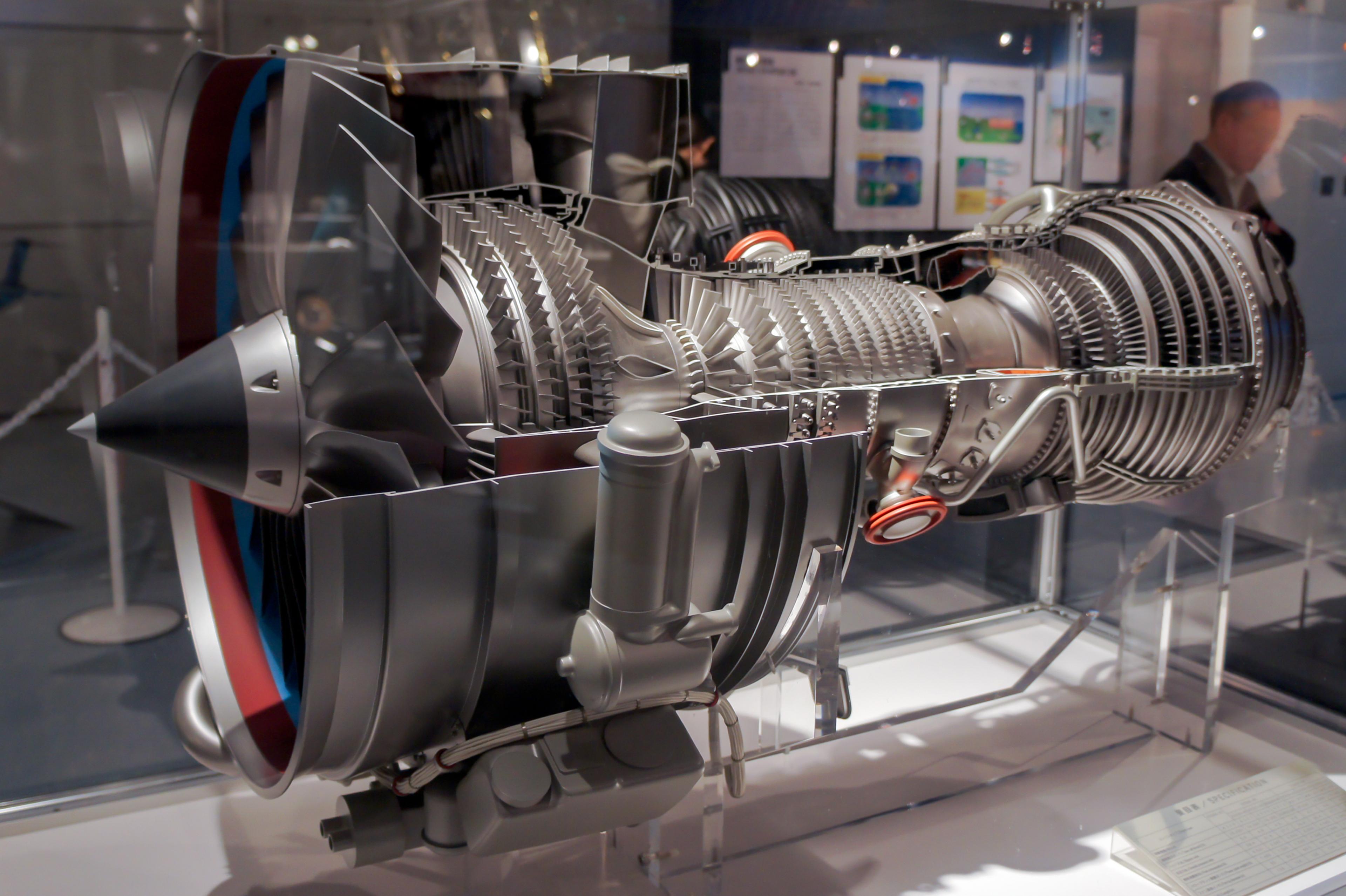

V2500 jet engine and its joint manufacturer IAE

In the early 1980s, Airbus was developing its breakthrough A320 jet. To break the near-monopoly held by GE’s CF6 and CFM56, four aerospace companies—Pratt & Whitney (PW), Rolls-Royce (RR), Germany’s MTU, and Japan’s JAEC—formed a joint venture called International Aero Engines (IAE). Their goal is to build a cleaner, more efficient alternative, the V2500 engine.

IAE’s structure was deliberate: PW and RR each owned 32.5%, MTU held 22.5%, and JAEC had 12.5%. PW leveraged RR’s reputation in Europe, and RR used PW’s deep connections in the U.S. market. Other than that, each firm specialized in one crucial component, sharing costs and risks: PW took the combustion chamber and high-pressure turbine, RR handled the high-pressure compressor, JAEC built fans and low-pressure compressors, and MTU specialized in low-pressure turbines.

IAE’s model succeeded spectacularly. Since its launch in 1993, over 7,000 V2500 engines logged 300 million flight-hours. But the very structure that propelled success also sowed tension. Any technical upgrade or strategy shift required shareholder consensus and decision-making was inevitably slow.

By the early 2000s, airlines urgently demanded improved fuel efficiency amid rising fuel prices and stricter environmental regulations. Pratt & Whitney had been secretly testing a revolutionary design since the 1990s: the Geared Turbofan (GTF). In a traditional jet engine, the large front fan and the low-pressure turbine are physically locked on the same shaft, so both have to spin at the same speed. But this is always a compromise: the fan operates most efficiently and quietly at slower speeds, while the turbine needs to spin much faster to extract the most energy from the hot gases. It’s like forcing a marathon runner and a sprinter to run at the same pace—neither performs at their best.

PW’s GTF broke the deadlock with a planetary gearbox between the fan and turbine. So that the fan can turn about three times slower than the turbine, letting both operate in their optimal range. Fuel efficiency improved by 16–20% compared to earlier engines in this class, and noise levels dropped by up to 75%, thanks mainly to the slower fan tip speeds reducing disruptive turbulence.

Pratt believed fiercely in this technology, investing billions through its parent company, United Technologies (UTC), to commercialize it. RR, however, expressed skepticism. They argued that the gearbox added complexity, weight, and risked reliability, preferring instead to refine their proven three-shaft architecture, optimized primarily for widebody jets. On the other hand, PW wanted full control. Sharing revenues evenly among four parties in IAE's joint venture was unappealing. Moreover, timing was critical. When Airbus unveiled the A320neo in 2010, they limited engine options to two providers. Coordinating a timely and agreeable partnership with RR seemed impractical. In 2011, PW purchased RR’s IAE shares for $1.5 billion, decisively shifting to a "Risk and Revenue Sharing Partner" (RSP) model rather than a traditional equity joint venture. MTU and JAEC became RSP partners contributing specific components and sharing revenues without governance control.

Post-split, PW’s PW1100G entered service in 2016 on the A320neo, capturing nearly 45% of market share. Ironically, in 2023, RR demonstrated the first ignition of its UltraFan engine, adopting the same geared-fan concept it once questioned. Now, RR actively seeks partnerships to re-enter the narrow-body market.